2017 Weak Key Generation Key Controversy

- 2017 Weak Key Generation Key Controversy Video

- Key Generator

- 2017 Weak Key Generation Key Controversy Youtube

- Key Generation Software

- 2017 Weak Key Generation Key Controversy 2017

- 2017 Weak Key Generation Key Controversy Lyrics

- Free Key Generation Software

- 2017 Weak Key Generation Key Controversy 2017

Fr. Martin is correct: a bridge must be built between the Catholic Church and those struggling with same-sex and trans-gender issues. But it cannot be built of tissue paper of 'suggestions' based on rhetorical questions and sophistry.

14, 2006- The USA Patriot Act seems headed for long-term renewal.Key senators have reached a deal with the White House that allays the civil liberties concerns of some critics of the law. James Martin's weak and wobbly bridge.' Catholic World Report (July 13, 2017). Reprinted with permission. Catholic World Report is an online news magazine that tells the story from an orthodox Catholic perspective. Its hard-hitting content is free to all readers without a subscription.

- Weak keys usually represent a very small fraction of the overall key space, which means that if someone generates a random key to encrypt a message, it is a rare condition that weak keys will cause a security problem. However, it is considered a good design for a cipher to have no weak keys.

- Humans have been asking for millennia: Where does new life come from? Religion, philosophy, and science have all wrestled with this question. One of the oldest explanations was the theory of spontaneous generation, which can be traced back to the ancient Greeks and was widely accepted through the Middle Ages.

The need for better 'rapport' between the Catholic Church and those who experience same-sex attraction, their friends and family, and the public at large is undeniable. Fr. James Martin, S.J. in his book Building A Bridge: How the Catholic Church and the LGBT Community Can Enter a Relationship of Respect, Compassion, and Sensitivity (HarperOne, 2017) attempts to offer some ways in which better relationships can be built.

The new normal

Since the 1990s it has been clear there is a new cultural and social atmosphere concerning 'same-sex' and 'trans' issues and, therefore, we need to do a lot of retooling to find a suitable terminology to explain Church teaching. This retooling has become necessary for many reasons. Foremost among them is the fact that the teaching of the Church is expressed in terms that are rooted in a philosophy — a teleological view of nature – a view that the body is good and we need to act in accord with the design of the body. Moreover many of those who identify as gay (or bisexual or trans or questioning) are 'out and proud', no longer discreet and no longer trying to 'fly under the radar'. My generation (the 'boomers') generally didn't realize or recognize that we knew gay people until we were in our twenties. But young people now have family members and friends who are attracted to members of the same-sex, who have been 'out' since middle school or so, and find it unexceptional and 'normal'.

This 'new normal' has some upsides. We no longer 'freak out' when we learn that someone we love identifies as gay. Few Catholics are tempted to ostracize gay people as being unfit for polite society. Rather, even those of us committed to the Church's teaching that homosexual acts are radically at odds with God's plan for sexuality, do not find it difficult to love, accept, and remain in relationship with those who are same-sex attracted. Undoubtedly we still have lots to learn but progress is being made. We remain somewhat confused about how to reconcile our love for them with our conviction that some of their choices are seriously sinful and a threat to their eternal salvation, not to mention a threat to their current physical and psychological health. But we face the same dilemma in respect to our loved ones who, for instance, have had abortions, who are cohabiting, or who are divorced and remarried without benefit of an annulment.

We remain somewhat confused about how to reconcile our love for them with our conviction that some of their choices are seriously sinful and a threat to their eternal salvation, not to mention a threat to their current physical and psychological health.

One of Martin's initial points is valid and important. He speaks with frustration of how more bishops did not make public statements condemning the June 12, 2016 killing of 31 people at the PULSE club in Orlando, known to be a 'gay' club. That horrific slaughter was the act of an individual who hated homosexuals, apparently because of his extreme Muslim beliefs. I agree with Martin on the point that too few Church leaders expressed their horror at the hatred that lead to such slaughter. Perhaps they were afraid their action would foment hatred of Muslims (all of whom, it should not be necessary to say, do not hate gays) and to cause more inter-religious strife, but this is the time for speaking the truth even in face of unwelcome consequences.

Furthermore, it is very welcome that Martin sees that bridges go two ways and appeals to the LGBTQ community to extend respect, compassion, and sensitivity to the Church. He offers some stern words about forms of disrespect that have issued from some members of the LGBTQ community and asks them to be sensitive to how demanding the lives of Church leaders are. Still, although he urges the LGBTQ community to listen carefully to Church authority, he never calls members of the LGBTQ community to fidelity to Church teaching. His remarks about priests and members of religious communities who are living lives of chaste celibacy were also welcome but should have provided an opportunity to call others to such faithful witness to the truths of the Gospel.

Missed opportunity

Yet, Martin's book, sadly, is a missed opportunity for building true bridges.

Indeed, it stands to do more harm than good in the enterprise of building bridges.

One major missed opportunity is that Martin doesn't acknowledge that many Catholics have been working for some time to build bridges with others in respect to same-sex issues, precisely because there are those we love with whom we want to stay in relationship — but to whom we also want to speak the truth. The work of such groups as Courage, Encourage, and Living Waters is not even mentioned. He says nothing about those brave souls who are managing to live lives of radical commitment to the Lord as they embrace the demands of chastity. The work of Andrew Comiskey, Daniel Mattson, Ron Belgau, Eve Tushnet, Robert Lopez, Joe Sciambra, Walter Heyer, among others, have opened new pathways for talking about the quest for holiness by those who have experienced same sex desires or the desire to 'be' the opposite sex. (Mattson, Tushnet and Sciambra have responded to Martin's book.)

Those individuals disagree on some important matters, but all agree that chastity is possible and all speak from their own experience. It is not that there is not much more to be done, but to fail to mention this ground-breaking work is to misrepresent the current state of affairs. (While there is much excellent bridge-building material available, a fairly comprehensive publication is the book I edited with Fr. Paul Check, Living the Truth in Love: Pastoral Approaches to Same-Sex Issues [Ignatius, 2015]).

At the outset, let me apologize for the length of this response to a book that is quite short (as it is essentially an expanded talk). Such a response is necessary, however, due to the many flaws and errors in Fr. Martin's book. Since my colleague Eduardo Echeverria has ably treated Martin's complete neglect of Church teaching about homosexuality in his CWR review 'Father James Martin, 'bridges' and the triumph of the therapeutic mentality' (June 16, 2017), I do not address that egregious flaw. Along with that serious omission is the lack of any attempt by Martin to do some of the work needed to show how respectful, compassionate, and sensitive the Church's teaching in regard to all sexual morality really is. Many good critiques of Martin's book have been done, among them articles by Fr. Gerald Murrayand Fr. Paul Mankowksi, and undoubtedly more will be written.

I want to look most closely at two of Martin's major points that are misleading too many people. Martin's insistence that we should call people by their preferred terms is more problematic than he allows, as is his claim that the Church treats members of the LGBTQ community differently from others who violate its teachings.

Using the preferred name

It is easy to agree with Martin's — somewhat facile — claim that it is important to address people as they wish to be addressed.

But that claim is only sometimes true and is difficult to apply when the individuals being described belong to a group for whom some 'anomaly' or 'special need' seems to define their existence and whatever terms we use seem to need frequent 'updating.' We keep changing the terms by which we refer to the mentally, emotionally and physically 'disabled' or 'challenged.' We have spoken in the past of the 'retarded', 'lunatics', 'cripples', etc. but who would use those terms now, except as insults? I suspect that these terms at one time were not meant to be offensive and not received as offensive but as time wore on they became so. Sometimes terms switch in the opposite direction: when I was young, to speak of homosexuals as 'queers' was considered maximally offensive, but now it is a term used in the academy for 'queer studies' and is proudly embraced by some, perhaps most, homosexuals.

Moreover, sometimes using the preferred terminology of the group one is engaging prejudices the conversation. To speak of a legal arrangement between those of the same sex who pledge to a lifetime relationship that involves sex as 'marriage' is to concede what is in dispute.

Yet, to insist that leaders of the Church and Catholic apologists 'respectfully' refer to people by the terms that conflict with Christian anthropology amounts, in my view, to asking them to violate their consciences.

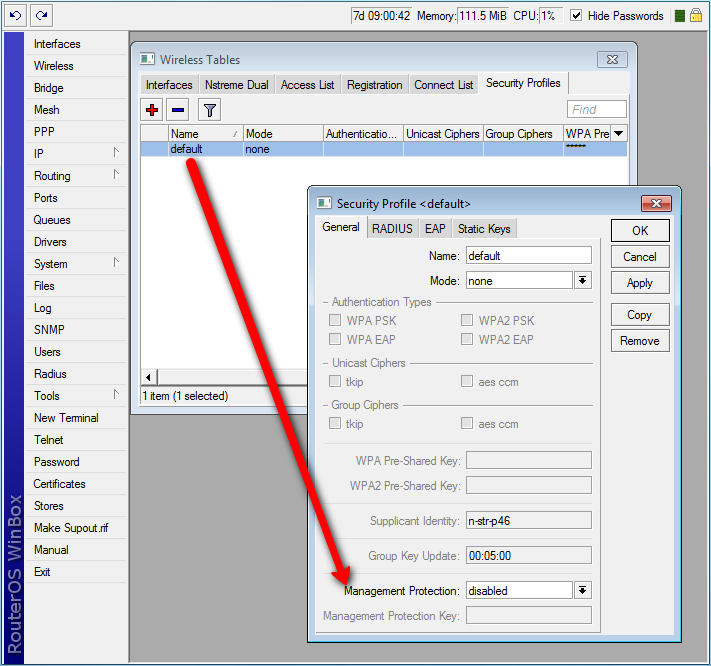

WPA is designed to work with all, but not necessarily with first generation.

Fr. Harvey, the founder of Courage, early on spoke of 'homosexuals' but later spoke of 'homosexual persons' because he did not want to label people by their sexual desires. Then he spoke of 'persons with homosexual desires' in order to emphasize that one's personhood should always be seen to be of foremost importance. He was trying to find terms that recognized the dignity of all individuals, and of their indelible status as beloved sons and daughters beloved by God. Justice requires acknowledging this effort to show respect, compassion, and sensitivity.

In recent years Courage has adopted the somewhat clunky phrase, 'persons who experience same-sex attraction'. For the most part, those who wish to speak of SSA persons (persons who experience same sex-attraction) are reluctant to use the word 'gay' since it carries connotations not true of all who experience SSA, such as advocacy for same-sex 'rights' to marriage or adoption of children. Yet, not everyone who identifies as 'gay' nor all those who use the word 'gay' mean the same thing by the word. Some chaste, devout Christians, speak of themselves as 'gay' to convey only that they have sexual attractions to members of the same sex, not that they are sexually active or that they promote 'gay' causes.

Martin adopts a practice that rivals the phrase 'persons with SSA' for its awkwardness: he speaks of 'LGBTQ people'. I doubt that anyone has ever introduced himself/herself/whatever self as an 'LGBTQ person' or spoken of 'LGBTQ' friends. Women call themselves 'lesbians' or 'gay' and men call themselves 'gay', and others speak of themselves as 'bi-sexual' or 'trans' — but never 'LGBTQ'.

It is not unproblematic to speak of 'LGBTQ' people, but those difficulties are never addressed by Martin. He refers to some uncontroversial instances that show it is right to use the 'name' preferred by people and seems to think that settles the issue. But the examples Martin gives to support his claim that we should address people as they chose to be addressed show a flair exhibited throughout the book — a flair for sophistry. He speaks of the change of names from Abram to Abraham and Simon to Peter (a change dictated by change in 'mission' or 'role') or of 'Negro' to 'African-American' (a change dictated by cultural accretions to the term 'Negro). But those instances bear virtually no resemblance to the use of 'LGBTQ' to refer individuals who are, to put it delicately, are not entirely comfortable with their biological personhood and the ethical demands that flow from it. Certainly, the leaders of the Church, Church documents and Catholics in general should not use terms that are perceived to be highly offensive to any group. I, for one, would like to see the term 'sodomy' (although Biblical and traditional) retired. In the past, it was more of a technical term, but those who generally use it today intend to be disrespectful.

Yet, to insist that leaders of the Church and Catholic apologists 'respectfully' refer to people by the terms that conflict with Christian anthropology amounts, in my view, to asking them to violate their consciences. To speak of a person as 'lesbian,' 'gay,' 'bisexual', 'trans' or 'questioning', is, in the eyes of the Church, to put the person in a 'box'; a 'box' that threatens to define people in terms of a tendency to sinful behavior or in fact a commitment to sinful behavior.

The Church, as it has made abundantly clear, does not understand a sexual attraction to a person of the same sex or the desire to 'be' another sex to be, in itself, a sin. Those desires, frequent or infrequent, latent or dominant, perceived to be inherent or acquired, when not welcome and when resisted, are not sins. They are in the same category as adulterous thoughts, racist thoughts, and greedy thoughts that are not welcome and are resisted. It is inconsistent with Christian anthropology to label people by their sins or their desires that could lead to sin. Yes, we speak of 'adulterers,' 'racists, and 'active homosexuals', as individuals involved in sinful behavior, but in no way do we intend to reduce them to these aspects of their being. The term 'LGBTQ' community does just that.

So what are we to do? Currently achieving the goal of a mutually agreeable term seems nigh impossible. The person who comes up with one might well deserve the title of 'genius diplomat' of the age. At the moment, the best I can come up with, for the purposes of this discussion, is to refer to 'those that Fr. Martin includes in the LGBTQ community.' That is altogether pathetic but perhaps it serves the function of not forcing me to use terms I can't accept and but also of building a bridge with Fr. Martin by using terms that he thinks are acceptable to those he includes in the LGBTQ community. For the purposes of efficiency I will use the imperfect acronym, FMLGBTQC to refer to 'those that Fr. Martin includes in the LGBTQ community.'

Selective termination?

Another central point of Fr. Martin's book is his claim that the Church treats FMLGBTQC differently from those who engage in other kinds of sinful behavior. (Note this amounts to a back-handed way of acknowledging that homosexual sex is sinful but I am not sure that Martin is aware of that implication). One response to the claim that a group is being singled out for treatment not directed towards other groups is to lobby that the other groups receive the same treatment as the group that has been singled out. But Martin is not lobbying here for the Church to become stricter in its terms of employment in respect to all sinners; he is complaining about the treatment of FMLGBTQC.

Martin acknowledges that 'church organizations have the authority to require their employees to follow church teaching.' He insists, though, that 'this authority is applied in a highly selective way.' He claims that 'almost all firings in recent years have focused on LGBT matters.' I have no idea what his source is for such a claim. Rarely do we know with any certainty why 'firings' and separations happen. That information must almost always come from the aggrieved party because it is illegal for employers to disclose private information. Certainly it is not hard to get the impression that the FMLGBTQC are being singled out for firings but that appearance can be explained by several factors. Sadly some homosexuals try deliberately to get fired since they want to challenge Catholic institutions in such as way as to 'shame' the institutions into violating their principles to avoid a public backlash. Those who do get fired, intentionally or not, are often quick to go to the media.

Martin's 'method' for arguing that the Church is wrong to treat the FMLGBTQC as it does is not to develop a rationale for that position but to raise a series of questions — quite obviously rhetorical questions — which suggest that for church organizations to be 'consistent,' they should refuse employment to all sinners and also anyone who does not fully embrace the teachings of the Church. He asks, 'Do we fire a straight man or woman who gets divorced and then remarries without an annulment?' … 'Do we fire women who bear children out of wedlock?'…'Do we give pink slips to those who practice birth control?' He also questions whether the Church is inconsistent in hiring non-Catholics since they do not 'fully embrace the teaching of the church'.

Let me respond to his rhetorical questions with one of my own: 'Does he seriously think this is a good argument?' Does he seriously think the Church fires homosexuals – and, in his view, homosexuals only – because they 'do not accept Church teaching'? Or is the matter more complicated than that? (I am making the technique of rhetorical questions my own!)

Let me ask Martin a non-rhetorical question: does he hold that Church organizations would never be justified in exercising their legitimate authority to fire some employees whose behavior is gravely immoral or who publicly advocate for practices and policies against Church teaching? He gives no instance of such. Still, I doubt Martin would object to firing the principal for having an affair with a faculty members, or firing a janitor who fills his closet with pornographic centerfolds. I can't know his position, because he doesn't state it, but I think it safe to speculate here.

What Martin fails to do is to engage what principles there may be behind the 'selective' exercise by church organizations of their legitimate authority to fire employees whose behavior is not consistent with Church teaching. He also fails to ask why Church organizations might believe it their duty to fire some employees for their immoral behavior and not others, to fire some for their beliefs and not others.

More and more institutions are requiring prospective employees to sign a statement of agreement that they will support and abide by Church teaching. Thus, those who are fired are being fired primarily for violating an agreement they made, one very consistent with the nature of their employment.

Martin would have done well to have noted that Catholic institutions often give robust explanations for the need to have faithful Catholics employed at such Catholic institutions as Catholic schools. The primary reason is that the faculty (and other employees) are to be role models for students. How can they be effective educators of Church teaching if they reject that teaching? More and more institutions are requiring prospective employees to sign a statement of agreement that they will support and abide by Church teaching. Thus, those who are fired are being fired primarily for violating an agreement they made, one very consistent with the nature of their employment.

But we should note, that in spite of the fact that many of those employed at Catholic institutions are clearly not living in accord with Church teaching, very few are fired. Why is that?

Generally Catholic organizations don't dig into the private affairs of people's lives; they do so only when an action becomes public and with certain proof. Often the firing is done with some considerable sensitivity — the sinner is asked to repent and sometimes is even offered recommendations for employment at a place where such behavior does not conflict with the goals of the organization.

Still, it must be acknowledged that there is a 'selectivity' concerning who gets fired. The 'selectivity', however, is not determined by the 'kind' of sin, but on the public nature of the sin and the ability of the authorities to substantiate the immoral behavior.

While I have no reason to believe Martin's claim that most of the firings in recent years have involved LGBT matters, I suspect it is true that those firings are the ones that most often make it into the public eye. As intimated above, others don't always or even usually make it into the public eye, because those who are fired for misbehavior don't care to make their sinful deeds made public. I know of a man, a 'devout' father of eight, at a prominent Catholic university, who was having an affair with an undergraduate, the daughter of another professor. They were seen daily at Mass together. They were also caught by campus police having sex behind a bush. He was given notice immediately. He did not go around telling people why he no longer taught there, but we all knew.

A very important point here is that many of us knew of the affair. His colleagues and students were scandalized. But how could we 'out' him? Had we gone to the president with our 'suspicions' what could the president have done? The reason most fornicators, adulterers, cohabiters, etc. are not fired by Catholic organizations is that their sins are not public. And even when they are well known, the organization usually prefers to look the other way, again, because of lack of certain proof but also because often these people are able and popular teachers and to fire them would make a mess; the reasoning, not always implausible, is that more harm than good would be done by firing them.

It is important to note that same-sex couples have often and perhaps usually received the same 'neglect'; both because if they didn't make their relationship public, most people didn't know, and those who did know couldn't really provide proof, as sharing the same domicile is not proof. There was such a case a few years ago at a Catholic girls' high school where a popular teacher, who was in a lesbian relationship, got pregnant through IVF. That she lived with her same-sex partner was well known, and known even by the principal, but when she asked for maternity leave and told the principal she had used IVF, she was fired – because her use of IVF and continued defense of her decision. She was the one who decided to make the issue known. Now, it is not unlikely that there were other individuals teaching at that same school who used IVF to get pregnant, and it is even possible that that fact was well-known, but was not known to the authorities in such a way that they were provoked or able to act upon their knowledge.

Let me note that it is wrong to fire an individual simply because that individual experiences same-sex attraction, just as it is wrong to fire someone simply for being tempted to engage in adultery. It is impossible to address every nuance in hypothetical situations that might necessitate different responses, but let me try not to step into too many potholes by first noting that unless a person reveals his temptations to us, it is nearly impossible for us to know what they are. But sometimes a person self-reports what is going on within them. Suppose diaries of a person tempted to homosexual attraction or to adultery came into the possession of an employer (here only a temptation is recorded, not an intent to act upon the temptation). The information alone would not justify firing a person but some descriptions of the temptations might make it prudent for an employer to carefully consider what responsibilities could be assigned to the individuals. Males known to have a nearly irresistible temptation to adultery, for instance, should not be given the task of chaperoning female high school students on over-night trips. And, indeed, his employment may be terminated if that responsibility is an important part of his job, a responsibility that could be delegated to no one else.

Getting caught is a good thing

Martin is adamant that it is unjust to fire homosexuals for their sinful behavior and not to fire others who sin, such as fornicators. Inconsistent application of policy is certainly wrong. But Martin seems unaware of a truth that is important to those seeking holiness: if one is a wrong-doer, it is good to be caught and good to face consequences for one's action. Indeed, the wrong-doer who is not caught and does not suffer consequences should be seen to experience greater harm. No one likes to get fired; no one likes one's wrongdoing to be made public. But the person to whom such happens is much more likely to reform his or her ways than the person who is not caught.

This point needs to be made: the 'firing' of such individuals is not so much to punish them for their wrongdoing; rather its chief purposes are to protect the innocent from being harmed by them, to teach those under the Church's care that such behavior is incompatible with Christian discipleship, and to prompt the wrong-doers to change their ways: the Church is all about helping people achieve holiness.

A similar kind of reasoning governed the decision by Bishop Paprocki to announce that canon law prohibits a funeral mass for those who have contracted a same-sex marriage.' (For an excellent analysis of that announcement see 'Bp Paprocki's norms on 'same-sex marriage' by my colleague Edward Peters.) Martin, rather than 'building a bridge' by explaining Church teaching, instead called 'foul' and used this as an instance of more selective enforcement of Church authority. What he should have done was to have explained that canon law 1184 (and 1185) prohibits ecclesiastical funerals for several classes of sinners, among them 'manifest sinners' for whom an ecclesiastical funeral would cause scandal to the faithful.' Note that the reason given for denying an ecclesiastical funeral is not to punish wrong doers, but that providing an ecclesiastical funeral would 'cause scandal' to the faithful.

The Church cannot and should not fail to teach the truth entrusted to it, to avoid offending people. Yes, respect, compassion and sensitivity are key Christian values, but so is truth.

What does this mean? Clearly the prohibition is not intended as a penalty for the deceased since they are now beyond the reach of canon law. The prohibition is meant to help the living, to help them recognize the wrongness of same-sex 'marriages.' To give the respect embedded in ecclesiastical funerals to unrepentant public sinners is wrong and misleading. Note that this prohibition does not apply to homosexuals per se, but to those unrepentantly publicly involved in a sinful situation, which same-sex marriage surely is. And not, of course, just to them but to all unrepentant public sinners. Paprocki spoke to this particular sin because our culture is currently obsessed with same-sex issues and is getting most everything wrong about them. For a culture to embrace same-sex 'marriage' is a frontal assault on Scripture and natural law.

Paprocki's announcement was undertaken to help Catholics realize the incompatibility of same-sex marriages with God's plan for sexuality. Martin could help build bridges by explaining this to those likely to misinterpret Paprocki and the Church. Both are concerned with the salvation of souls and Martin should use the platform he has been given to demonstrate how bridge-building can best be executed.

Again, Eduardo Echeverria has demonstrated how Martin completely neglected to present Church teaching in his book. That failure makes for very wobbly bridges, since for true dialogue to take place, honest discussion must take place. The Church cannot and should not fail to teach the truth entrusted to it, to avoid offending people. Yes, respect, compassion and sensitivity are key Christian values, but so is truth.

A challenge to Martin: radical bridge-building

I would like to challenge Martin to do some of the bridge-building he advocates — some of the most radical bridge-building that needs to be done. I have never been to a gay parade or bar or a gay bash on the beach but the few pictures I have seen and descriptions I have read make it clear that they are disgusting, orgiastic bacchanalias. (I have always been impressed with the recommendation of one psychologist to parents of adult children who have adopted the 'gay' lifestyle, that they go with their adult offspring to the parades and bars and sex fairs so their offspring experience how their choices and experiences look through their parents' eyes.)

Few people are willing to attend vile gay events, but those few people — well, really, the one person, Joe Sciambra — an ex-gay porn star — and the few intrepid individuals he enlists to join him, who dare to enter those dens of iniquity, do so to take the love of the Gospel into places where it is desperately needed, though generally viciously rejected. Sciambra and others go there to convey Christ's love to those who hate themselves so much that they submit themselves to such degradation. Yes, they are not representative of the whole of the FMLGBTQC but they are souls — souls in need of the Good News that they are loved and that Jesus died for them.

Yes, Fr. Martin is correct: a bridge must be built between the Catholic Church and those struggling with same-sex and trans-gender issues. But it cannot be built of tissue paper of 'suggestions' based on rhetorical questions. It must be built of steel and concrete, of a bracing commitment to truth and true love, mingled, of course, with respect, compassion and sensitivity.

Acknowledgement

Janet E. Smith. 'Fr. James Martin's weak and wobbly bridge.' Catholic World Report (July 13, 2017).

Reprinted with permission. Catholic World Report is an online news magazine that tells the story from an orthodox Catholic perspective. Its hard-hitting content is free to all readers without a subscription.

The Author

Janet E. Smith holds the Father Michael J. McGivney Chair of Life Ethics at Sacred Heart Major Seminary in Detroit. She is the author of Living the Truth in Love: Pastoral Approaches to Same-Sex Attraction, In the Beginning . . .: A Theology of the Body, Life Issues, Medical Choices: Questions and Answers for Catholics, The Right to Privacy (Bioethics & Culture), Humanae Vitae: A Generation Later and the editor of Why Humanae Vitae Was Right. Prof. Smith has received the Haggar Teaching Award from the University of Dallas, the Prolife Person of the Year from the Diocese of Dallas, and the Cardinal Wright Award from the Fellowship of Catholic Scholars. She was named Catholic of the Year by Our Sunday Visitor in 2015. Over a million copies of her talk, 'Contraception: Why Not' have been distributed. Visit Janet Smith's web page here. See Janet Smith's audio tapes and writing here. Janet Smith is on the Advisory Board of the Catholic Education Resource Center.

Copyright © 2017 Catholic World Reportback to top

Learning Objectives

- Explain the theory of spontaneous generation and why people once accepted it as an explanation for the existence of certain types of organisms

- Explain how certain individuals (van Helmont, Redi, Needham, Spallanzani, and Pasteur) tried to prove or disprove spontaneous generation

Clinical Focus: Anika, Part 1

Anika is a 19-year-old college student living in the dormitory. In January, she came down with a sore throat, headache, mild fever, chills, and a violent but unproductive (i.e., no mucus) cough. To treat these symptoms, Anika began taking an over-the-counter cold medication, which did not seem to work. In fact, over the next few days, while some of Anika’s symptoms began to resolve, her cough and fever persisted, and she felt very tired and weak.

- What types of respiratory disease may be responsible?

We’ll return to Anika’s example in later pages.

Humans have been asking for millennia: Where does new life come from? Religion, philosophy, and science have all wrestled with this question. One of the oldest explanations was the theory of spontaneous generation, which can be traced back to the ancient Greeks and was widely accepted through the Middle Ages.

The Theory of Spontaneous Generation

The Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BC) was one of the earliest recorded scholars to articulate the theory of spontaneous generation, the notion that life can arise from nonliving matter. Aristotle proposed that life arose from nonliving material if the material contained pneuma (“vital heat”). As evidence, he noted several instances of the appearance of animals from environments previously devoid of such animals, such as the seemingly sudden appearance of fish in a new puddle of water.[1]

This theory persisted into the seventeenth century, when scientists undertook additional experimentation to support or disprove it. By this time, the proponents of the theory cited how frogs simply seem to appear along the muddy banks of the Nile River in Egypt during the annual flooding. Others observed that mice simply appeared among grain stored in barns with thatched roofs. When the roof leaked and the grain molded, mice appeared. Jan Baptista van Helmont, a seventeenth century Flemish scientist, proposed that mice could arise from rags and wheat kernels left in an open container for 3 weeks. In reality, such habitats provided ideal food sources and shelter for mouse populations to flourish.

2017 Weak Key Generation Key Controversy Video

However, one of van Helmont’s contemporaries, Italian physician Francesco Redi (1626–1697), performed an experiment in 1668 that was one of the first to refute the idea that maggots (the larvae of flies) spontaneously generate on meat left out in the open air. He predicted that preventing flies from having direct contact with the meat would also prevent the appearance of maggots. Redi left meat in each of six containers (Figure 1). Two were open to the air, two were covered with gauze, and two were tightly sealed. His hypothesis was supported when maggots developed in the uncovered jars, but no maggots appeared in either the gauze-covered or the tightly sealed jars. He concluded that maggots could only form when flies were allowed to lay eggs in the meat, and that the maggots were the offspring of flies, not the product of spontaneous generation.

Figure 1. Francesco Redi’s experimental setup consisted of an open container, a container sealed with a cork top, and a container covered in mesh that let in air but not flies. Maggots only appeared on the meat in the open container. However, maggots were also found on the gauze of the gauze-covered container.

In 1745, John Needham (1713–1781) published a report of his own experiments, in which he briefly boiled broth infused with plant or animal matter, hoping to kill all preexisting microbes.[2] He then sealed the flasks. After a few days, Needham observed that the broth had become cloudy and a single drop contained numerous microscopic creatures. He argued that the new microbes must have arisen spontaneously. In reality, however, he likely did not boil the broth enough to kill all preexisting microbes.

Lazzaro Spallanzani (1729–1799) did not agree with Needham’s conclusions, however, and performed hundreds of carefully executed experiments using heated broth.[3] As in Needham’s experiment, broth in sealed jars and unsealed jars was infused with plant and animal matter. Spallanzani’s results contradicted the findings of Needham: Heated but sealed flasks remained clear, without any signs of spontaneous growth, unless the flasks were subsequently opened to the air. This suggested that microbes were introduced into these flasks from the air. In response to Spallanzani’s findings, Needham argued that life originates from a “life force” that was destroyed during Spallanzani’s extended boiling. Any subsequent sealing of the flasks then prevented new life force from entering and causing spontaneous generation (Figure 2).

Figure 2. (a) Francesco Redi, who demonstrated that maggots were the offspring of flies, not products of spontaneous generation. (b) John Needham, who argued that microbes arose spontaneously in broth from a “life force.” (c) Lazzaro Spallanzani, whose experiments with broth aimed to disprove those of Needham.

Think about It

- Describe the theory of spontaneous generation and some of the arguments used to support it.

- Explain how the experiments of Redi and Spallanzani challenged the theory of spontaneous generation.

Disproving Spontaneous Generation

The debate over spontaneous generation continued well into the nineteenth century, with scientists serving as proponents of both sides. To settle the debate, the Paris Academy of Sciences offered a prize for resolution of the problem. Louis Pasteur, a prominent French chemist who had been studying microbial fermentation and the causes of wine spoilage, accepted the challenge. In 1858, Pasteur filtered air through a gun-cotton filter and, upon microscopic examination of the cotton, found it full of microorganisms, suggesting that the exposure of a broth to air was not introducing a “life force” to the broth but rather airborne microorganisms.

Later, Pasteur made a series of flasks with long, twisted necks (“swan-neck” flasks), in which he boiled broth to sterilize it (Figure 3). His design allowed air inside the flasks to be exchanged with air from the outside, but prevented the introduction of any airborne microorganisms, which would get caught in the twists and bends of the flasks’ necks. If a life force besides the airborne microorganisms were responsible for microbial growth within the sterilized flasks, it would have access to the broth, whereas the microorganisms would not. He correctly predicted that sterilized broth in his swan-neck flasks would remain sterile as long as the swan necks remained intact. However, should the necks be broken, microorganisms would be introduced, contaminating the flasks and allowing microbial growth within the broth.

Pasteur’s set of experiments irrefutably disproved the theory of spontaneous generation and earned him the prestigious Alhumbert Prize from the Paris Academy of Sciences in 1862. In a subsequent lecture in 1864, Pasteur articulated “Omne vivum ex vivo” (“Life only comes from life”). In this lecture, Pasteur recounted his famous swan-neck flask experiment, stating that “life is a germ and a germ is life. Never will the doctrine of spontaneous generation recover from the mortal blow of this simple experiment.”[4] To Pasteur’s credit, it never has.

Figure 3. (a) French scientist Louis Pasteur, who definitively refuted the long-disputed theory of spontaneous generation. (b) The unique swan-neck feature of the flasks used in Pasteur’s experiment allowed air to enter the flask but prevented the entry of bacterial and fungal spores. (c) Pasteur’s experiment consisted of two parts. In the first part, the broth in the flask was boiled to sterilize it. When this broth was cooled, it remained free of contamination. In the second part of the experiment, the flask was boiled and then the neck was broken off. The broth in this flask became contaminated. (credit b: modification of work by “Wellcome Images”/Wikimedia Commons)

Think about It

- How did Pasteur’s experimental design allow air, but not microbes, to enter, and why was this important?

- What was the control group in Pasteur’s experiment and what did it show?

Key Concepts and Summary

Key Generator

- The theory of spontaneous generation states that life arose from nonliving matter. It was a long-held belief dating back to Aristotle and the ancient Greeks.

- Experimentation by Francesco Redi in the seventeenth century presented the first significant evidence refuting spontaneous generation by showing that flies must have access to meat for maggots to develop on the meat. Prominent scientists designed experiments and argued both in support of (John Needham) and against (Lazzaro Spallanzani) spontaneous generation.

- Louis Pasteur is credited with conclusively disproving the theory of spontaneous generation with his famous swan-neck flask experiment. He subsequently proposed that “life only comes from life.”

Multiple Choice

Which of the following individuals argued in favor of the theory of spontaneous generation?

- Francesco Redi

- Louis Pasteur

- John Needham

- Lazzaro Spallanzani

2017 Weak Key Generation Key Controversy Youtube

Key Generation Software

Which of the following individuals is credited for definitively refuting the theory of spontaneous generation using broth in swan-neck flask?

- Aristotle

- Jan Baptista van Helmont

- John Needham

- Louis Pasteur

Which of the following experimented with raw meat, maggots, and flies in an attempt to disprove the theory of spontaneous generation.

The Default key name is 'idrsa' and that is what ssh will look for. At least for me.In my case, the name of the key is different for every server and, for reasons I cannot understand, the ssh system only wants to look for 'idrsa'. I think the config file is not having an effect.

- Aristotle

- Lazzaro Spallanzani

- Antonie van Leeuwenhoek

- Francesco Redi

2017 Weak Key Generation Key Controversy 2017

Fill in the Blank

The assertion that “life only comes from life” was stated by Louis Pasteur in regard to his experiments that definitively refuted the theory of ___________.

Show AnswerTrue/False

Exposure to air is necessary for microbial growth.

2017 Weak Key Generation Key Controversy Lyrics

Think about It

Free Key Generation Software

- Explain in your own words Pasteur’s swan-neck flask experiment.

- Explain why the experiments of Needham and Spallanzani yielded in different results even though they used similar methodologies.

- What would the results of Pasteur’s swan-neck flask experiment have looked like if they supported the theory of spontaneous generation?

2017 Weak Key Generation Key Controversy 2017

- K. Zwier. 'Aristotle on Spontaneous Generation.' http://www.sju.edu/int/academics/cas/resources/gppc/pdf/Karen%20R.%20Zwier.pdf↵

- E. Capanna. 'Lazzaro Spallanzani: At the Roots of Modern Biology.' Journal of Experimental Zoology 285 no. 3 (1999):178–196. ↵

- R. Mancini, M. Nigro, G. Ippolito. 'Lazzaro Spallanzani and His Refutation of the Theory of Spontaneous Generation.' Le Infezioni in Medicina 15 no. 3 (2007):199–206. ↵

- R. Vallery-Radot. The Life of Pasteur, trans. R.L. Devonshire. New York: McClure, Phillips and Co, 1902, 1:142. ↵